Here are the key events in the timeline of the Glencoe Massacre:

Late January 1692

Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon and around 120 soldiers from the Earl of Argyll's regiment arrive in GlencoeAlmost two weeks

The soldiers are hosted by the MacDonalds, as was customary in the HighlandsFebruary 12, 1692

Glenlyon and the other officers receive orders to kill the MacDonalds of GlencoeFebruary 13, 1692 at 5 AM

The signal is given to attack, and the massacre beginsAfter the massacre

40 women and children die from exposure while trying to flee the Glen in the snow

The Glencoe Massacre is considered one of the most infamous acts in Scotland's history. It was a premeditated and brutal attack on people who had welcomed the soldiers into their homes.

The Massacre of Glencoe

Details: Part of the Jacobite rising of 1689

Date: 13 Feb 1692

Location: Glen Coe, Argyll, Scotland

Sides: Kingdom of Scotland Clan MacDonald of Glencoe

Commanders/ Major Duncanson Alasdair Maclain

Leaders Captain Glenlyon

Colonel Hamilton

Colonel Hill

Strength: 920 men Unknown

Casualties: None about 30 KILLED

A Site of Human Tragedy

Glen Coe is a truly atmospheric valley to walk, cycle or drive. It is also the site of a renowned but commonly misunderstood human tragedy. Romanticized during the 19th century as a clan feud between the Campbells and the MacDonalds, the real story behind the Glencoe Massacre is much darker. It has often been described as state-sponsored slaughter in pursuit of political ambition.

Who Ordered the Massacre at Glen Coe

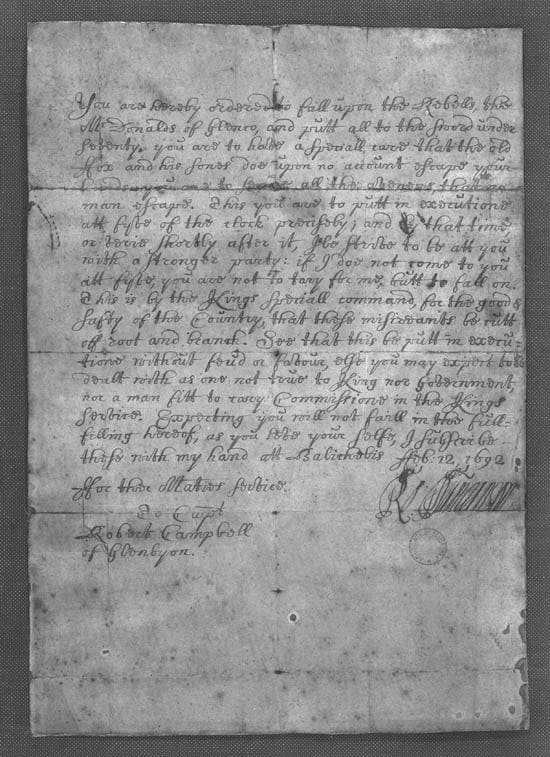

Pictured is a copy of the order that reached the regiment on the eve of the massacre. It was signed by Major Robert Duncanson on the eve of the massacre at Ballachulish, to the west of the Glen.

The original army order is supposed to have stated that all men under 70 be slain, however, the Secretary of State at the time, John Dalrymple, had influence and changed the wording to ‘extirpate’, or kill, all. It is said that King William III approved all orders, and by the time it reached the soldiers, the command was to wipe out all the MacDonalds of Glencoe under the age of 70, ensuring none escape, especially not the clan MacDonald chief, MacIain, and his sons.

It is believed that Campbell of Glenlyon was drinking and playing cards with the chief’s sons when the order arrived. He excused himself, and each officer was in turn, withdrawn from their host’s home to be given the command for the following morning. The time of 5am was set to coordinate with supporting troops from the north and south, blocking escape routes and assisting in the massacre.

In the aftermath, there were tales of attempts to warn the MacDonalds that night, of a Campbell piper playing a lament and of a soldier warning a dog to sleep away from the house in the heather. Possibly, some soldiers risked their own lives to alert their hosts. They may also have known that two officers from the regiments in Fort William had already been sent to Glasgow for court-martial after refusing to have anything to do with the command.

When Was the Glencoe Massacre

The Glencoe Massacre occurred at 5am on the 13th of February, 1692. The most commonly accepted account is that the Scottish army massacred 38 men, women and children of the clan MacDonald of Glencoe. A further 40 died of exposure attempting to flee the Glen in the snow.

Soldiers from the Earl of Argyll regiment had been billeted with the MacDonalds, ostensibly as a way of gathering unpaid tax, a common practice at the time. The 120 quartered (or hosted) soldiers would have been welcomed into the clan’s homes as the hospitality culture dictated.

Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon was in charge of the regiment, though Captain Thomas Drummond was the only officer in the regiment to know of the real reason for their presence in the Glen when they moved in a couple of weeks before. The rest of the command only knew their orders the night before the massacre.

What Happened at the Glencoe Massacre

The massacre took place in the townships (groups of small farms or crofts) the length of the Glen. The 120 troops under the command of Campbell of Glenlyon split into smaller bands.

The Massacre Itself

It is said that the clan chief MacIain was shot in the head whilst dressing, with his wife brutally attacked and probably raped before she fled into the hills to later perish in the snow. Another account tells of the heartless killings of a toddler and an old man and also of a man being nearly clubbed to death before fire was set to the house he had crawled into to escape.

Snow hampered the arrival of the supporting forces and their plan to block escape from the Glen to the north and southeast. Thus the remaining MacDonalds could flee, although some would later die of exposure. Many, including the clan chief’s sons, escaped into Stuart country in Appin, while others hid in Coire Gabhail or the Lost Valley.

After the Massacre

When the troops eventually arrived from Fort William by way of the Devil’s Staircase, the massacre was done, and the bodies buried. MacIain was buried at the clan’s ancestral burial ground on the island of Eilean Munde in Loch Leven.

Although some 200 families lived in Glen Coe, nothing remains of the dwellings of the day. Some of the MacDonalds returned to the Glen, but during the 18th and 19th centuries, people were removed from the Glen as part of the Highland Clearances. Stones from abandoned buildings would have been taken to build new structures over the years, like walls and enclosures for sheep.

Situated to the northeast of Loch Achtriachtan, in the township of Achtriachtan, the buildings have been recently excavated by the National Trust for Scotland, and they have also uncovered evidence of crop cultivation.

Why Were the MacDonalds of Glencoe Killed

There are three main reasons behind the massacre.

Jacobite Rebellions

The first rebellion dates back to the Glorious Revolution in 1688, when William and Mary took the crown from James VII of Scotland and II of England and Ireland. Although a ‘glorious’ and peaceful rebellion in England, in Scotland a counter rebellion was organised by John Graham, viscount of Dundee, who was loyal to the then exiled James, or Jacobus in Latin. This gave the term Jacobite or supporters of James. The battle took place at Killicrankie and the Jacobites won, although it was a bloody battle on both sides, and the viscount was killed.

A further Jacobite uprising was, therefore a considerable threat the throne. A garrison to enforce law and order in the Highlands was established at Inverlochy, which was renamed Fort William, after the king. However, with the proximity of the army base to Glen Coe, the MacDonalds were unlikely to mount any sort of rebellion.

Prejudice

Secondly, the MacDonalds were an easy target to be made an example of. The MacDonalds of Glencoe were a sept or subgroup of the MacDonald clan. They had a dark reputation spanning decades for being unruly and lawless. Rustling contributed to their earnings, and reputedly stolen cattle were taken to the Lost Valley where they were easily protected from reprisals from other clans. Lowlanders were also prejudiced against the Highland Gaelic-speaking clans, seeing them as uncivilised barbarians.

James VII is the last Catholic king to rule, and many of his Jacobite supporters from across the kingdom were both Catholic and Episcopalian. Presbyterianism was the main religion of both monarchs and church governance at that time. It is thought that the MacDonalds of Glencoe were Episcopalian or possibly Catholic, therefore a threat to governance.

The Oath of Allegiance

The third reason was the oath of allegiance to William and Mary, the new monarchs. It is said that this was demanded of all subjects; however, in a bid to get the Highland clans on their side, chiefs had been invited to sign by the 1st of January 1692 and take a share of £12,000. Those who did not sign would be punished. In all accounts, there were many delays in circulating the oath. For example, William III was in Flanders, and it took time for his approval to arrive.

It is believed that, like many clan chiefs, MacIain waited until he was released from his previous oath to James VII. This only arrived in December 1691, a few weeks before the deadline for the oath. Once MacIain heard he was free to swear allegiance to William III, he made his way to Fort William. However, no sheriffs were there, and the nearest officer able to sanction his allegiance was south in Inveraray, where he duly went. His signature missed the deadline by a couple of days.